Even the most ardent fan of elasticated waistbands would have to concede that 2020 has been an ugly year for fast fashion. The industry’s environmental issues are well known. It emits more carbon emissions than all international flight and maritime shipping combined, according to UNEP, the UN Environment Programme. The UK alone sends an estimated £140m worth, or 350,000 tonnes, of used clothing to landfill. And 2020 highlighted the human cost of over-production, with grim reports from Pakistani factories supplying clothes to Boohoo topping off a year in which garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam were among the first to pay the price of the pandemic as western companies refused to pay for orders.

But there has been good news too, even within the limitations of this strange, sad year – sometimes because of them. Here are five promising developments – from mindset shifts to disruptive technology – which could help us emerge from this wearing something we can feel good about.

Secondhand and DIY fashion

In an expression of collective stuffification, two in five people in the UK had a Covid clearout, a real problem as charity shops received more goods than they could handle. The silver lining was a boom in secondhand shopping: Depop had a stellar year, with traffic up 200% year-on-year and turnover doubling globally since 1 April. Ebay sold 1,211% more preloved items in June than at the same time in 2018, with a dramatic 195,691% rise in purchases for secondhand designer fashion during the same period.

There was a sense of make do and mend in designer fashion too, as disruption to the supply chain – and a mountain of unsold garments and fabric – helped propel the trend for using “deadstock” (fabric which may otherwise go to waste). Small brands such as Gemma Marie The Label and Justine Tabak bought abandoned fabric to make bespoke pieces for clients over Instagram, and designers including JW Anderson made clothes using fabrics and trims from previous seasons.

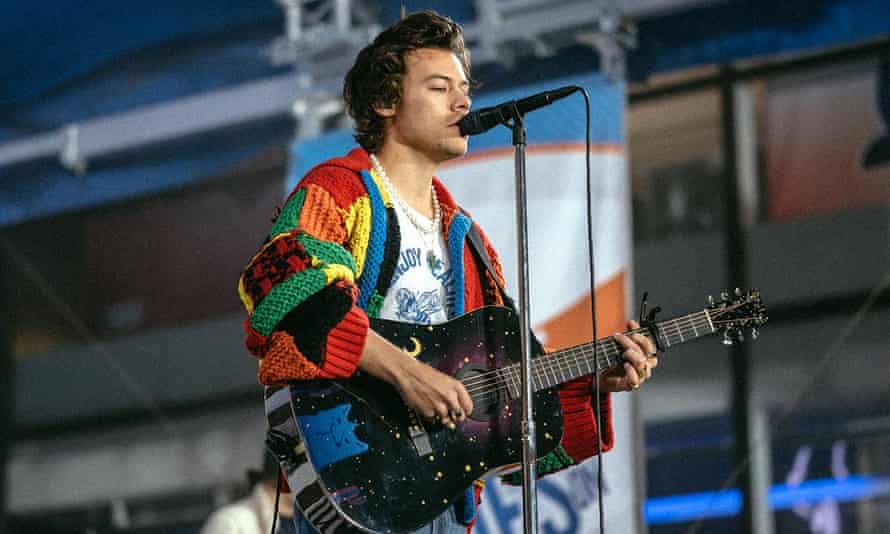

Some used lockdown to make not sourdough bread but their own clothing, with handmade and DIY fashion up by 30% on Depop between May and July, and tie dye omnipresent. A TikTok trend for crochet, sparked by fans trying to recreate a multi-coloured cardigan worn by Harry Styles, was so pronounced that the V&A acquired the knit for its permanent collection.

Algae sequins and other sci-fi adventures

One promising 2020 project was the One X One incubator programme, organised by sustainability consultancy Slow Factory Foundation and Swarovski with support of the UN, which paired designers and scientists to produce prototypes for the industry.

Given the environmental cost of standard plastic sequins, fans of the disco-ball look may be cheered by its collaboration between Phillip Lim, a New York-based designer worn by Michelle Obama, and designer and researcher Charlotte McCurdy, who worked together to produce a shimmering cocktail dress with sequins made from ocean macroalgae, a material which sequesters carbon.

“With a little back of the envelope math, the carbon dioxide that has been trapped inside of the sequins of this dress by the algae would fill 15 bat

htubs,” says McCurdy. If the wearer composts the dress at the end of its life, about 50% of the carbon captured “can reasonably be expected to remain trapped in the soil”. Crucially, however, the dress represents “a vision of actively doing good, rather than striving to be less destructive. A dress made of algae sequins points to a future where fashion can be a negative emission technology.”

The incubator also paired up Dao-Yi Chow and Maxwell Osbourne, of the New York label Public School, and scientist Dr Theanne Schiros to create lab-grown “bioleather” trainers.

Though the project was set up before the pandemic, the limitations of 2020 led to even more innovation and ingenuity. Schiros was often unable to access materials grown in her lab, for example, so she approached a local kombucha brewery for byproducts with which to grow the bioleather.

“We literally grew a pair of sneakers – we collaborated with microbes!” says Schiros, who believes the collaboration produced unprecedented results in colour and texture. What’s more, she added, they are “back yard compostable,” for the ultimate in circularity.

Digital fashion

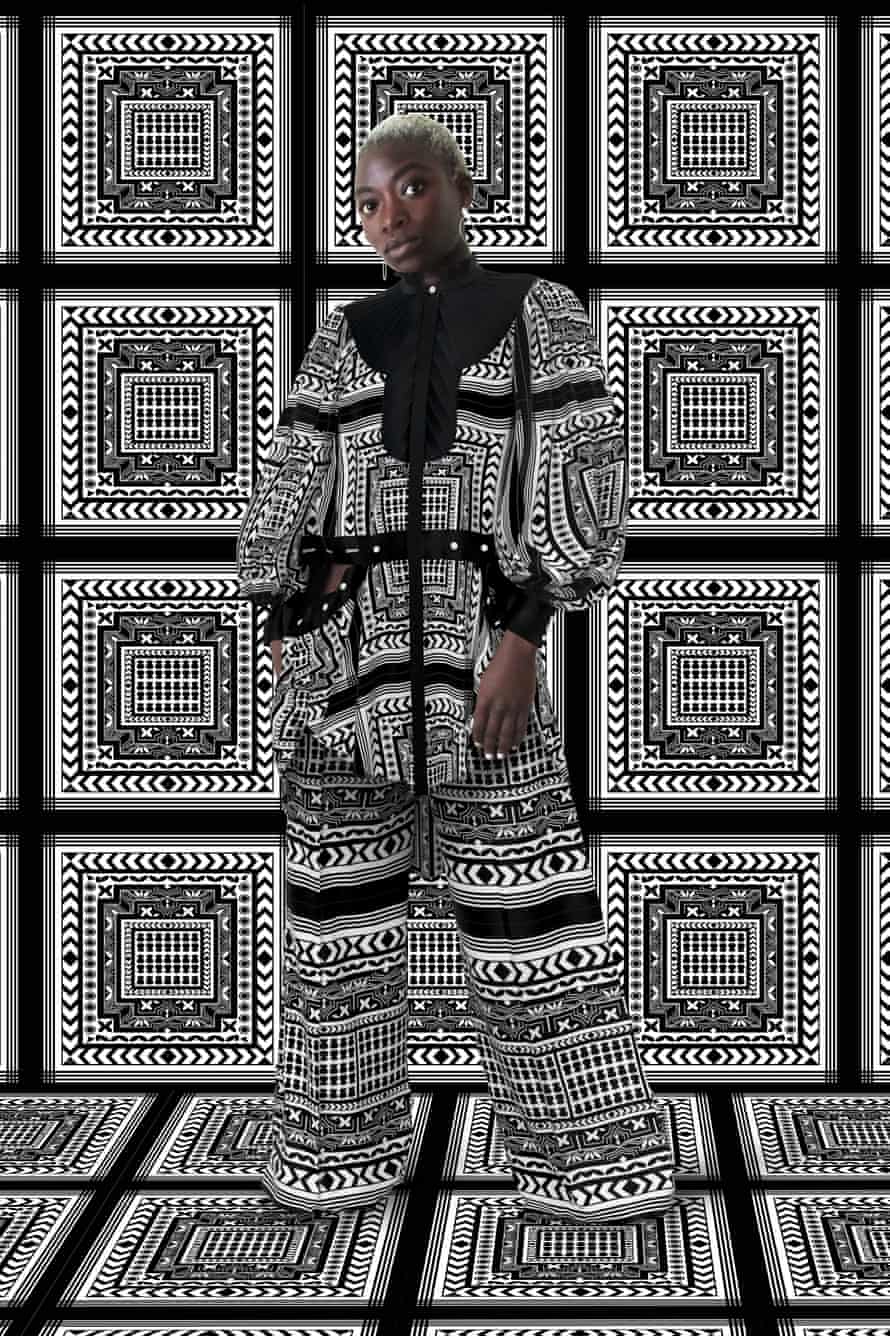

With traditional fashion shows often impossible, owing to social distancing, many brands produced digital showcases instead. One upside was that it wasn’t always the designers with the deepest pockets, with slots on traditional Paris or Milan fashion week schedules, who made headlines. Some small designers captured the imagination using digital fashion: circular fashion advocate, designer Anyango Mpinga and virtual fashion designer Yifan Pu, for example, created some of the most memorable digital fashion images of the year.

And none of the big brands could beat Congolese designer Anifa Mvuemba’s internet-melting Hanifa virtual show, on Instagram Live, which married a powerful film on the impact of mining on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with 3D renderings of six ghostly, spotlit looks undulating down a pitch-black catwalk.

A focus on ‘ethical’, not just ‘sustainable’, fashion

In 2019, many fashion brands were keen to talk about sustainable fashion – trumpeting garments made from recycled plastic bottles – but rarely mentioning workers’ rights. In 2020, awareness of workers, and their woefully perilous position, was inescapable. Dana Thomas, author of Fashionopolis, says this year was a moment of truth. “We saw brands cancel their orders in Bangladesh – orders that were already made – and refuse to pay for them, sending workers home from the factories broke and starving.

“The #PayUp campaign on social media, which shamed some of those brands into paying their bills, showed how the power of the people could force effective and necessary positive change in the industry. It was infuriating to see the brands welch, but heartening to see social pressure work.”

During the same period the Black Lives Matter movement has also shone a light on the industry’s racist practices, with many of its institutions pledging to change.

“Covid-19 has really laid bare some inequalities,” says Margo Alexandria of Custom Collaborative, a nonprofit dedicated to redesigning the fashion industry by helping create careers for low income and immigrant women, “and while we would not of wished for it we accept it as a partner in some ways. Companies consider their workforce in a way they didn’t before.”

capital of the fashion industry, share in the wealth they create.” Photograph: Myesha Evon Gardner

In a third collaboration, produced by the One x One incubator, Custom Collaborative teamed up with designer Mara Hoffman to develop a framework for apprenticeships aiming to “level the playing field in the fashion industry by ensuring that the women of colour, whose labour constitutes the working capital of the fashion industry, share in the wealth they create.” The idea is to give these women access to training, in order that they may have fulfilling careers within sustainable fashion – or may become entrepreneurs themselves – rather than allowing them to be hired solely for entry-level jobs and never given the training, or opportunity, for promotion. The framework created is ready to be rolled out to the industry at large.

A mindset shift

For sustainable fashion expert and writer Aja Barber attitudes towards consumption went in two directions during the pandemic. On the one hand, she says, lockdown has meant “we don’t feel the need to put on a new outfit every day.”. On the other, some people have felt the need to buy stuff to make them feel better. “The most important thing for me is to pick apart those habits because, we are literally in lockdown, do you need a new dress? Probably not.”

The long-term impact – whether we will see Chinese-style “revenge shopping”, with post-pandemic queues snaking away outside shops full of people spending lockdown savings – remains to be seen.

In fast fashion, the idea, driven by some parts of the industry, that clothes can be on-trend one season and hopelessly passe the next will be dented by the gigantic mound of excess stock – an estimated €140bn to €160bn – which is currently floating around from unsold spring/summer collections. Some companies, such as Next, have “hibernated‘” these clothes, and plan to release them in the spring.

We can all play our part in what comes next, says Slow Factory founder and creative director Celine Semaan, who sees the pandemic as “almost a fire drill,” for a world upended by climate crisis. “It has also showed necessity of embarking on sustainable journey because we have no other choice.” It has also caused us to question what’s important and will surely spark a change in culture. “And the way culture changes is important,” says Semaan, “because policy follows culture.”

More Stories

Selective Information on Purchasing Diamond Jewelry

Jennifer Lopez Wows in Indian Fashion Designer Outfit

Which Skirt Is Right For You?